CLOCKING OUT

the ill-starred birth of digitalism

What year is this?

This past week, we have spoken of the Second and Third Industrial Revolutions, which we have dated as being from approximately 1850-1930, corresponding with the rise of the railroad and managed corporation, and 1940-2008, corresponding with the rise of the global consumer economy and the rise of a managerial, profit-participating elite.

What era are we living in now? The Fourth Industrial Revolution, most likely. It is hard to say for sure. Iteratively, it makes sense. New technology is emerging. Each period opened and closed in a time of great crisis. These crises were not just political in nature, but related to a global system of production for living. 2007-2008, as we all know, was a period of extreme unction for the manager-as-owner, for everyone with a bit of a stake in the world in fact.

What characterizes the era in which we live? How will it fare? What will happen to the manager, the star of this strange odyssey across the centuries?

Fear, computers, circles

First, what characterizes today.

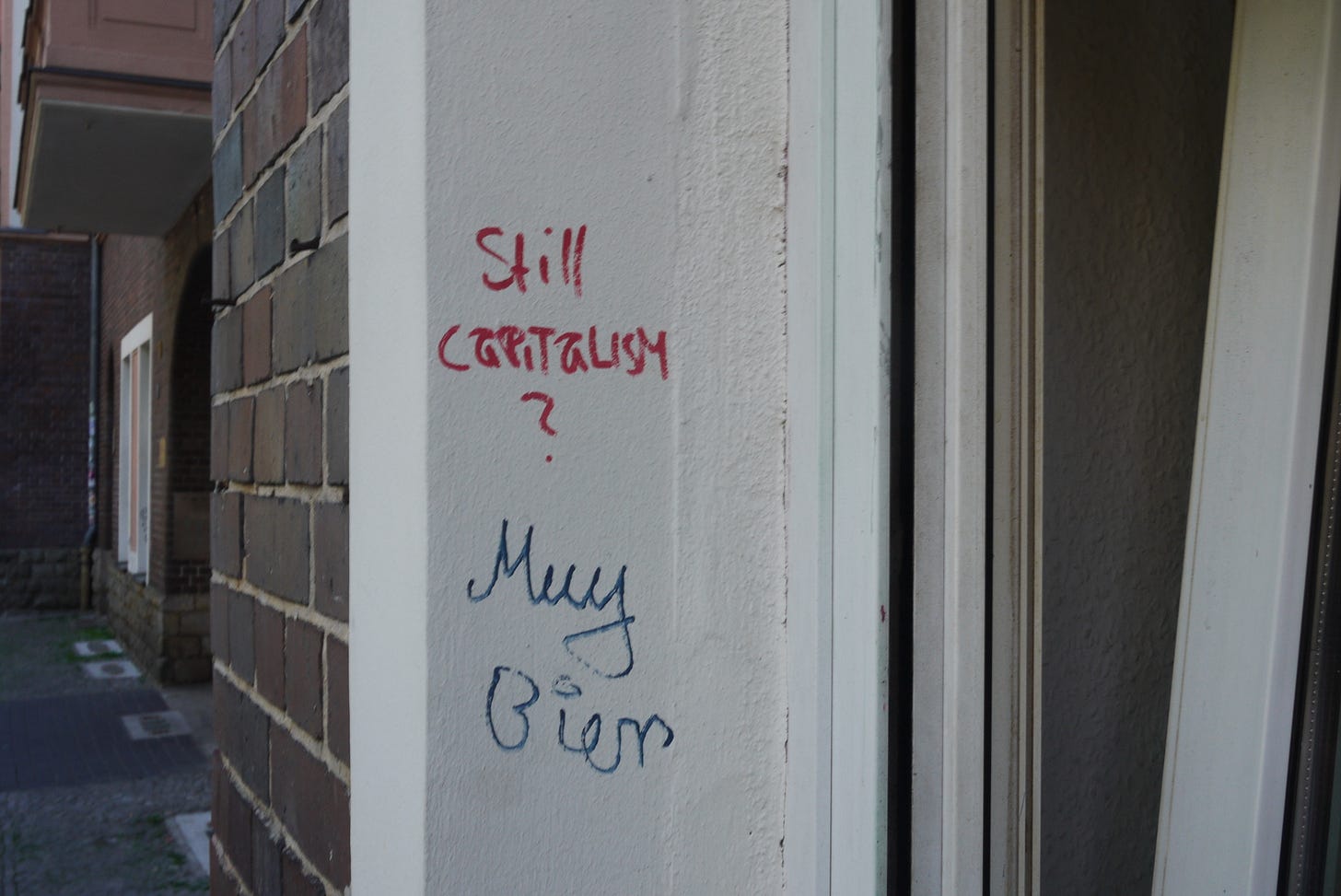

Fear. Many call it precarity. It’s fear. Precarity is a relationship of fear, fear that the world will disappear tomorrow. It is a distinctly unchristian fear, and it is a distinctly modern one. It is political, it is economic, it is fractal, reflected across layers in society, growing from the same fundamental function.

Computers. Digitalization, it’s called, the relentless drive to virtualize and make all business processes live on computers. Without a doubt, these new thinking machines, their production at ever more material-efficient and cutting edge processes are the core of the world economy and life.

Circles. Cyclization, or iteration, has become a recurrent trend for management and product development, and has become core. The relentless capture and need for analysis has produced a new circular motion of the world production machine. It has enabled for operational processes in businesses to become ones of learning, growth and verification. Cyclical iteration as social process produces the fundamental need for accreditation (to validate cycles), which separates the laborer from the professional. As a production process, it subjugates the consumer to a node in the product lifecycle. Cyclical iteration from the perspective of a product-in-itself turns everything into another try, never perfected or whole. Cyclical iteration is the chase of asymptotic perfection.

Corporate Fear of a Woke Planet

Management had discovered in the 1970s (the Nestle boycott springs to mind) that they were in fact quite vulnerable to morally-driven protest movements. Insofar as the field of political contestation moved to the world of private ownership and business, it had exposed itself unduly to a troubling reality—they had a weakness governments did not.

Governments are in all but extreme cases protest resistant by design. You are not very able to deprive a government of its lifeblood without putting yours at risk. Business on the other hand faces a very different arrangement of forces—continued revenue growth is the justification for and fixed star of success for the business elite.

Boycotts, the threat of boycotts, the image of the company, all of these mattered profoundly. Companies should by necessity appear neither moral nor immoral. Corporations exist in a bizarre reverse Machiavellian space, because even in monopoly conditions, non-consumption is a viable possibility. For the prince, it is best to be both feared and loved, and if you can only be one--better to be feared than loved for a prince. For a corporate body, it is better to be neither loved nor feared, and better to be loved than feared if you must be one.

Corporations are in a uniquely precarious position. Above and beyond the direct threat of market action against them, by the 1980s investment markets were not driven necessarily by pure rationality, but by trend-based, game-theoretical rationality. To maintain market confidence, investment and ensure their own compensation and status, managers must make their business’ revenues continually grow.

You will own nothing

One effective way of resolving corporate precarity was so simple and so potent that the fact that it only emerged so late in the history of the corporation is astonishing.

Contracting! Not that it hadn’t existed before—but boy did it change. Suddenly you had disciplined and ready workforces in Asia ready to work for little and with no blame attachable to the corporate body necessarily. The history of outsourcing may not be particularly long, but it is certainly a history of a profound, fear-driven compromise.

Contracting became a staple of work in developed markets as well. It was necessary to restore worker discipline after thirty years of glory had made life so easy and earning your bread so simple. Fear is the first step in creating discipline, and discipline the first toward control.

Unions went, spent by their long alliance with organized crime but also because labor cost arbitrage made breaking them trivial. Stable work became less common, wage growth flattened, and right-to-work laws became commonplace, as permanent and stable positions became less and less common. Ask an adjunct about it. But their union won’t help them.

Precarity, or the economic relationship characterized by fear, is the necessary creation for a world where production must be wrung out of comfortable and free-spirited people. A world where employees can own nothing is a world where they can build nothing of their own. But this isn’t union propaganda. The real question is, why is precarity such a topic now?

New Precarity

Computers have opened up entire new kinds and dimensions of fear. The gig worker, the Uber driver, the DoorDasher, the 2 year contract worker, the just-under-full-time sort of part timer. They are the protagonists of the horror movie in cities.

While something like the gig economy has existed for as long as wage labor has been around, it is also a new level of contingency and automation that is applied to it, bizarrely, at the management level.

The history of automation has been one of unit-produced-level labor saving that serves a counterproductive effect of only enlarging the scope, scale, and intensity of labor in the long run. A jackhammer necessitates 100 men jackhammering to build more road than has ever before been seen in a place. Uber, DoorDash, Eleme, Meituan, TaskRabbit, Schmucks, $andycrotch, etc., all of these different labor platforms ‘solve’ a fundamental problem in labor that has historically always been handled by humans: the division and ordering itself of labor.

It is no small irony that the taxi dispatcher could be replaced by a program decades before anything approaching a human-level self-driving car could be created. The task of being a cab driver had long since been precarious, strangely managed, but the driver was, somehow, the most skilled labor involved, and remains, though they certainly are not compensated this way.

The rise of the gig economy post 2008 is not just the sign of the times, it is the sign of the increasing automation of management processes that are relatively simple. Without it, the scale and scope of the gig economy would produce on its own a secondary boom of what used to be temp services, and with them the according managerial level professionals administering the division of labor. In the end, the manager, like the bureaucrat they descended from, is in many places an avatar of process. Managers may yet survive in their role as accommodators, mediators, and exception handlers—but we’ll see.

Liberated brain cells

Specific management tasks such as taxi and freight dispatch were indeed automated, and in the destructive sense. There is no training a taxi dispatcher to build apps. Not without fucking over all the equally deserving app makers.

But, the digital revolution and everyone having computers, the arrival of the mobile broadband data network the flood of normies to the Internet, had a salutary effect. Everyone had a lot more time to dick around at work, especially if you have an office job.

It has also created an addictive cycle of engagement with the devices that was beginning to be exploited and came of age in the Obama administration. The uniquely American social media behemoths now dominate an incredible amount of people’s freed-up time and energy.

This is an interesting process! An incredible amount of intellect was collectively let loose, but fundamentally as a kind of waste or by-product from work gains in efficiency and productivity. No business has yet figured out how to direct, adequately, this excess capacity, and attempts often fail. It is in fact current wisdom that wasting time and offering a luxurious, low-pressure, low-time commitment work environment is in fact the best way to harness talent. The 4 day work week, the liberated and plush office environs of the Valley, even the encouragement of recreational drug use I the form of nootropics and their illicit cousin psychedelics all speak to the fact that clearly, it doesn’t take all that much time to create certain things.

To optimally make use of the unoccupied brain cells of society, they should instead be yoked to an apparatus for relentless surveillance and data-gathering. This captive activity will inform product designers and content creators as part of a circular motion from firm, to product, to consumer, to firm.

Spinning in place

The revolution in data collection and retention has proven to be the core economic value in personal computing services and cheap, holistically interactive multimedia radio networks. This was certainly counterintuitive—the bicycle of the mind’s actual value was always in the knowing of the roads taken. Perhaps this is true, but it points to a fundamental flaw in the digital economy. Cyclical iteration is the fundamental basis of the logic of this society that is digitalized. Work is done, data is collected, work is improved. It’s a far cry from the logic of the Marxist business, and for most people, profit is simply an immaterial thing, or a positive factor in the development of the product.

For many processes of cyclical iteration (science, art, education, cooking) the goal is abstract. But for a corporation, the goal is typically very tangible. For a management process, it is almost certainly tangible, or at least monetizable. The business service or product. The consulting service. The website, or web-app. The app! The physical product itself, is also trapped in this cycle of iteration.

Cyclical iteration is goal-oriented and goal-delimited. To consider this a bit more clearly, under what circumstances could the iPhone (A) be wholly different, or serve a new need, from the iPhone (A+1)? The product has expanded in scope, it has expanded in features. But it has spun in place, faster and faster.

Why should the iPhone become different from itself? Perhaps it should not. I use an iPhone, it is a good smartphone and it accomplishes its tasks admirably, and many of them are socially necessary for life.

The real question is, how much social progress has been missed by recreating and perfecting the television and putting it in people’s pockets? How much technological progress has there truly been in the past 50 years? Are there new technologies for propulsion? Are there new technologies for travel? What new materials have been discovered?

The world’s production machine is locked into a cycle of cyclical iteration and has seemingly stopped looking for new frontiers in development and paradigmatic technological shifts have become less common. The bulk of private research capital appears to be in lithography and software technologies for Internet services.

Watching for growth

Global economic progress then appears to mostly be a fiction that is hung around these 3 trends, fear, digitalization, and cyclical iteration in production. The number of firms responsible for gains in the NYSE has shrunk to a few—Tesla, Apple, Alphabet, Meta, Microsoft, Amazon, Netflix.

This is the core contingent of the incipient fourth industrial revolution. It is built on a society that surveils. The surveillance of everyone, at all times, for increasingly petty reasons. User experience improvement is the most typical one these days.

Growth is guaranteed by surveillance. Surveillance creates fear in equal measure with security or a perception of safety. Surveillance gives us the data captured for cyclical product development, which is the key to creating addictive and charismatic digital and high-tech products that ensnare the user and command their freed-up thoughts.

But these products, for all the wealth they have created, have also generated profound social and environmental externalities, have they not?

Return of the public agent

ESG is the return of the concept of the corporation as public agent. It is a way for the manager-as-owner, now possessed of boundless wealth and the apogee of their historical power, to redeem their wealth. The manager is a socially responsible creature, whose decisions affect employees and production. Production is a global process, with global consequences.

Corporate responsibility is a bizarre commitment to make—again, because corporations are, unlike governments, not protest-resistant. The first technique, contracting, to mitigate visibility of externalities, worked quite well.

Then, people started jumping off the roofs at Foxconn/Hong Hai Precision Industries. It became increasingly clear where the hell coltan and rare earths metals might just be coming from, and they’re warzones in Africa. Shell games don’t work on marks for long. So contracting working as long as it had was a happy coincidence.

Companies need then to come up with a new distraction. And the appearance of action is certainly one of them. It helps that it comes from some unimaginably big pile of money like BlackRock! The world’s richest bunch of fucks is trying to manage portfolios to save the planet. The tycoon has become a series of institutional investors, networks of erstwhile tycoons, using management to pursue boundless wealth and dictating what growth markets are.

This could very well be the solution for this problem of technological freeze and a paranoid, fearful society that is bizarrely allocating the gains from information technology.

Industry 4/Industry Die

It’s happening

Industry 4.0. Even the name bespeaks its origin, harnessing the power of computing technology to open up new sectors of growth.

There are some obvious proposed social changes that are growing happily out of these trends of fear, computers, and cyclical iteration. Own nothing, be happy. The manager-as-owner not only redeems themselves, but assumes control of anything large enough to want money. Data-driven evaluation and auditing for conforming with the social values of the managers and managers-as-owners. The development and perfection of AI to replace low-skill labor and low-value management (and ultimately, perhaps all human labor). The professionalization of the workforce. The development of digitalization until it encompasses the whole of society. Using these gains alongside the development of ‘green’ technology to create new polluting industries, such as wind and solar.

It is a society of control, relentless surveillance. It is a society of naked fear, where the control of every part of life is used to augment and perfect a system of production that has become essentially frozen.

Can it be finished?

It’s unlikely.

AI’s promise is real, but the general purpose AI seems to be as far away as it has been. Self-driving cars are still decades away. Automation in management has thus far been in the field of algorithmically driven tasks with little in the way of predictive intelligence. Perfected management systems have yet to truly arrive even amongst humans.

‘Green tech’ has scare quotes for a reason. While solar has gotten more cost-effective, it is still low-efficiency, and extremely polluting in the long run, as is wind power. Green technology is not likely to solve pollution or produce energy stably in many societies.

The real flaw in the system that we are approaching right now is the fact that it relies on a stable global system of labor cooperation, and the portability of the desires of the global elite manager class. It stands on a shaky ground in terms of politics, a weak ground in terms of computer science and energy technology as well.

But it might happen.

All the money in the world is going to buy something.

Let’s hope it’s not what it wants.